This March, I had the pleasure of being a curatorial volunteer at the Whanganui Regional Museum’s moa collection. This is one of the most important collections of moa bones in the world, much of it excavated from the Taranaki region Makirikiri swamp in 1938.

As a technical communicator with a geology/paleontology degree in her past, I was there with two goals: to start processing and recording their epic moa bone collection for both physical and online curation, and to document this process for future volunteers. There are many potential tasks for a curatorial volunteer at the museum. I could groom the mammal taxidermy, help sort out the insect collection, process frozen native bird specimens as “feather maps” or into skins for Maori cloak weavers, or clean beautiful vintage cases and line them with acid-free material so they could be used again. But I wound up spending most of this visit focused on my two main goals.

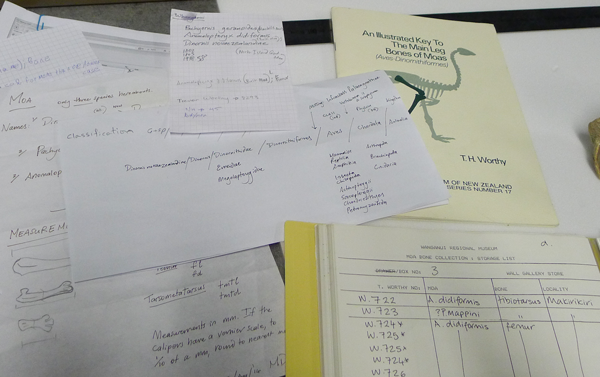

Writing up the moa bone processing procedure was a classic documentation and usability task. I began with this set of notes, a scientific guide to moas and moa bones, and a demonstration from the curator, paleontologist and giant flightless bird expert Dr. Mike Dickison. The moa bones had last been reviewed and documented by a researcher in 1989, Dr. Trevor Worthy, who had helpfully assigned numbers and site locations to them. I needed to enter data about each bone into the museum’s Vernon database, including length and diameter measurements, species types, condition, and the location where it was discovered.

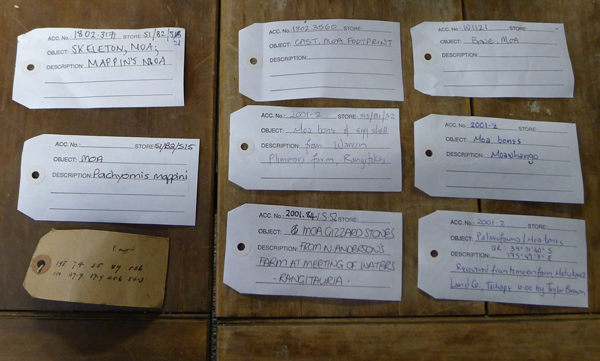

One goal of this project is ensuring that the recorded information is complete and consistent, even when different people are entering it. These labels, attached to individual bones, show documentation variations amongst different scientists and volunteers. The documentation we created includes examples as style notes for the volunteers, to show them how to be consistent.

After processing and entering data about the bones for a day, taking my own notes, I drafted a guide. Dr. Dickison gave me feedback. We refined the document through the rest of my volunteer week as problems came up and alternative procedures emerged.

In the documentation, we provided checklists in the documentation of what volunteers needed to know to get started, what the moa species in the collections were called today after species name changes, and the basics of scientific specimen measurement and photography.

After I – a communications professional – misspelled Anomalopteryx didiformis for the seventeenth time while entering data, we realized we had a usability issue for volunteers. So we examined the Vernon software and worked out a procedure that included templates for the main moa species. Now, volunteers select a species template and enter measurement, bone type, and location data, with shortcodes for entering many values. Not only did this reduce errors significantly, it halved the processing time for each moa bone.

We also came across issues around maintaining the integrity of the moa lab space. For example, food is not allowed in the moa lab, for two reasons. It is a small space that needs to be kept clean to preserve the integrity of specimens. In addition, the museum is full of Maori taonga and it is poor protocol to have food in the same spaces, even if you are just carrying it through the space that hosts the taonga. So, we needed to let volunteers know immediately about the food protocols for the moa lab.

Along with the paleontological privilege of working intimately with such a fantastic collection, it was great to see my data entry work making a difference – as soon as I finished a box of bones, it went on display in the “living collection” moa room, and Dr. Dickison gave me a chocolate fish.

Apart from my work with the moa collection, Dr. Dickison gave me a look at the museum’s collections behind the scenes, especially the insect collection and some hidden historical murals. I also helped groom the museum’s famous “Hetty the Hen” for her Easter stint giving candy eggs to the children of Whanganui. This was a great way to meet the friendly museum staff, as the whole team came out to move and install Hetty. Over my breaks, and on the days before and after, I explored Whanganui’s shops and galleries during their Open Studio week.

Some questions that Dr. Dickison answered for me:

Does the museum have a lot of moa skulls?

No – skulls were one of the most fragile parts of the moa skeleton. In fact, generally, if there was a skull the rest of the skeleton was present in good enough shape to reassemble. Most of these complete skeletons were discovered in caves, and most of them had been discovered, assembled and shipped to museums by the 1930s. The majority of the WRM collection consists of moa leg bones.

Some of the bones have been drilled for DNA samples. Can moas be cloned?

There are two problems with cloning moas. First, birds overall are more difficult to clone than mammals. Right now our cloning technology involves implanting eggs with genetic material in host animals to be carried to term. It’s very difficult to change the genetic material inside a hard shelled bird egg by the time it’s identifiable as an egg, but it’s relatively easy to do this for mammal egg cells.

Second, there is no genetic relative of a comparable size to a moa to be a host animal. The moa’s closest living relative is the South American tinamou, which, at its largest, is the size of a kiwi, about 2 kg – too small to be a host for even the smallest moa.

Does the museum need more volunteers to help with the moa bone collection?

Yes! Smart, interested people who live in the Whanganui area are welcome to participate. Ideally, volunteer stints will be 3 – 4 hours a day sorting out, measuring, photographing, and data entering moa bones. Visitor volunteers are welcome to apply – as a visitor I stayed at the nearby Tamara Lodge – and local volunteers are invited to set up regular stints in the moa lab.

It was a wonderful return to paleontology for me, an interesting technical communication experience, and a great “geekcation” overall. My thanks to Dr. Dickison and the Whanganui Regional Museum for including me in this project.

3 responses to “Volunteering at Whanganui Regional Museum’s Moa Collection”

Hi Emily,

That is completely fabulous – I’m so envious! I particularly love the way you identified the problem of consistency and solved it, leading to better quality data entry AND faster processing times. That is such a very important way that technical communicators can add value.

Nice work 🙂

Em

Great experience Emily. I’m jealous!

A great article about very useful work – thought-provoking and really interesting. Thanks!